Michelangelo Pistoletto, all’anagrafe Michelangelo Olivero Pistoletto (Biella, 25 giugno 1933), è un artista, pittore e scultore italiano, animatore e protagonista della corrente dell’arte povera. Inizia nel 1947 come apprendista nella bottega del padre restauratore di quadri, con cui collabora fino al 1958. Contemporaneamente frequenta la scuola di grafica pubblicitaria diretta da Armando Testa. Già in quegli anni ha origine la sua attività creativa nel campo della pittura che si esprime anche attraverso numerosi autoritratti, su tele preparate con imprimitura metallica e successivamente su superfici di acciaio lucidato a specchio. L’ausilio degli specchi nelle opere di Pistoletto rappresenta la volontà dell’artista di sfruttare la terza dimensione, lo spazio, e soprattutto il tempo.[senza fonte] Sfera di giornali (1999), opera “stabile” di Michelangelo Pistoletto; GAM di Torino.

La sua opera Venere degli stracci, del 1967, ne costituisce un emblema. « […] Come intellettuale il suo ruolo è stato quello di intrecciare uno spartito europeo di contatti tra artisti, facilitando la mostra delle Armi di Pino Pascali [nel gennaio del 1966 a Torino] e la conoscenza dell’arte italiana, mediante la creazione del Deposito D’Arte Presente e, in seguito, di una collezione d’artista, quanto rendendo possibile il dialogo tra gallerie, in particolare Ileana Sonnabend e Gian Enzo Sperone, che ha dato avvio alla circolazione della Pop Art in Italia e dell’Arte Povera in Francia, Germania e Stati Uniti.» (Germano Celant, Un’avventura internazionale)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia See more

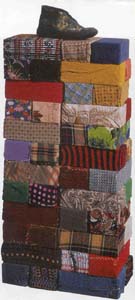

Oggetti in meno è stata una mostra allestita a Torino dall’artista biellese Michelangelo Pistoletto tra il dicembre 1965 e il gennaio 1966. È considerata basilare per lo sviluppo dell’Arte povera, teorizzata di lì a breve da Germano Celant. Con queste opere, come ad esempio i quadri specchianti, l’autore intende coinvolgere lo spettatore facendolo diventare protagonista dell’opera. Concetto teorico alla base dell’esposizione

Presenta opere molto diverse tra loro che sembrano non appartenere tutte allo stesso autore. È evidente un’anti-omogeneità (non c’è dunque una ricorrenza stilistica identitaria). Le forme, i temi e i materiali delle opere non sono quindi eterogenee fra loro. Anzi, le opere sono evasive: non si capisce bene né la loro origine né la loro destinazione proprio perché formano un insieme incomprensibile di elementi diversi tra loro, che non ha senso neanche se i suoi stessi elementi si sommano assieme.

Il senso di questa incertezza d’origine e destinazione fa sì che ciascun oggetto manifesti una sua genericità, senza uniformarsi agli altri della mostra ma semmai accentuando la singolarità del “proprio esserci”. Si parla quindi, riguardo alla mostra, di un “aggregato di singolarità generiche”. È come se il creativo provocasse un cortocircuito, che manifesta la distanza tra le stesse opere, e tra l’opera completa e l’autore.

L’identità autore appare dunque instabile. Anche l’insieme degli oggetti non appare come un uno, ne come una confluenza degli uno nei molti (è una molteplicità). L’inconsistente insieme di elementi è sinonimo della realtà. La comunità, infatti, è talmente caotica che le affinità e le differenze tra i suoi componenti non sono regolabili o concettualizzabili tramite la ragione. Non nascondendo la sua incompletezza, l’insieme degli oggetti genera continui scarti tra i propri componenti, tra quest’ultimi e l’insieme e tra insieme e tutto il resto. Avviene così che il tutto si definisce, paradossalmente, grazie al riconoscimento di una comune non-relazione che li lega. Sono paradossalmente legati dalla loro reciproca distanza.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia See more

Visit his official website See more

”To be a true ecologist [artist] today, one must re-establish the aesthetics of beauty within the realm of human trash and material waste.” –Slavoj Žižek (…maybe Žižek wouldn’t mind the minor alteration.)

Michelangelo Pistoletto pushed together a pile of rags & a statue of Venus in 1967 & 74. The above photograph is by the Belgian photographer Zeno de Cock from an exhibit in his hometown of Antwerp. Zeno’s photo captures the immediacy of the profound assemblage.

Venus of the Rags is redolent of the radical sixties & it is also an icon of Italian Arte Povera. Arte Povera was young & getting started when Pistoletto created the Venus. The sculpture speaks to a few key ideas of the style. Arte Povera is seen as anti-modernist, in that it (ostensibly) rejected the idealistic (high-modern) minimalism of the time. Conversely, it shared the reductive (minimalist) language that attempted to distill art to its essentials, its elemental basics & the bare minimum (albeit without the assumed sterility of some American minimalism). Arte Povera (loosely: poor art) was not necessarily an aesthetic of impoverishment, rather it was getting back to essentials—reaching to nature, the mundane, the everyday, even to classical antiquity (thus anticipating post-modernism) & also back to classic art materials (wood, marble & gold among others).

Pistoletto posed a dialectic with the discarded rags & a concrete cast replica of (Bertel Thorvaldsen’s) Venus (with the apple). Thorvaldsen’s Venus is holding an (unseen) apple & is from the legend “the Judgment of Paris.” The legend is not addressed by Pistoletto, however the goddess of love & beauty (Venus) was awarded the golden apple by Paris (remember too, Paris gave into her irresistible bribe of a beautiful woman). The significance resides in the symbol of Venus as beauty (ideal beauty). The rags are from Pistoletto’s studio & were used to clean his signature stainless-steel mirrors. We know that Pistoletto made several versions of the sculpture, including a live performance & he also made a gold (gilt) version.

This is an artwork of contrasts & reflection. We have high art coupled with an upsurge of refuse. Beauty’s facing rejected trash. Simple nudity is amidst an overload of used-garments. Refinement married to disgust. If we take the sculpture as a metaphor, it is an easy stand-in for our own confrontation with our now omnipresent waste. Venus of the Rags is a emblem to throw-away culture. It is as if she’s urging us to consider the aesthetic of decay & how that can inform a new & timely (re)consideration. Why should we care about our waste? What is important about the dialectic: beauty vs. trash?

We’ll also recall Pistoletto’s mirrors. While Venus isn’t looking into a mirror, she is looking at a polarity with which she’s part of. Other sculptures show where Pistoletto has taken classical statuary & positioned it with a real mirror suggesting that the statue were made for this purpose—made for reflection & contemplation.

Venus of the Rags is dialogue of the present with the ancient, resulting in a new perspective (dare I say a globalizing view) that includes the banal & everyday with the beautiful. Germano Celant (who coined the term Arte Povera) writes on Pistoletto’s Venus (specifically addressing the rags). The rags represent: “…the confusion & multivalence of marginalized people, the totalities of random & disparate communities of social rejects…that is the rags of society.”

Now we’re at another confrontation: the world’s wealthy contrasted with the poor. Again the artwork assumes a broader relevance. How do we regard the poor?—or the rich for that matter? We know these enormous questions need our attention & we know that art can help us see clearly (not only in a strict visual sense), more fundamentally, & then perhaps ethically. Art positions our problems to be observed, before we can understand them.

It is a great teacher/master who can create a didactic sculpture that is fresh & engaging (40-something years later). Pistoletto’s “poor art” perennially inspires growth & interaction. We know that Michelangelo Pistoletto continues to make art & he’s opened a foundation: Cittadellarte-Fondazione Pistoletto, where he proposes “a new role for the artist: that of placing art in direct interaction with all the areas of human activity which form society.”

Aurelio Madrid